Letters from Baghdad

Dustin Chase

It’s hard to imagine a woman in the early 1900’s forging ahead in a man’s world like Gertrude Bell did. Born in 1868 into a family of means, Gertrude Bell early on set her sights on places far from her native England. She was always cheeky, and when she graduated from Oxford, she was sent to relatives in Tehran with the hope that a more conservative culture could rein her in. Little did her parents know that she would fall in love with the Middle East and spend most of the rest of her life there in an activism they couldn’t imagine.

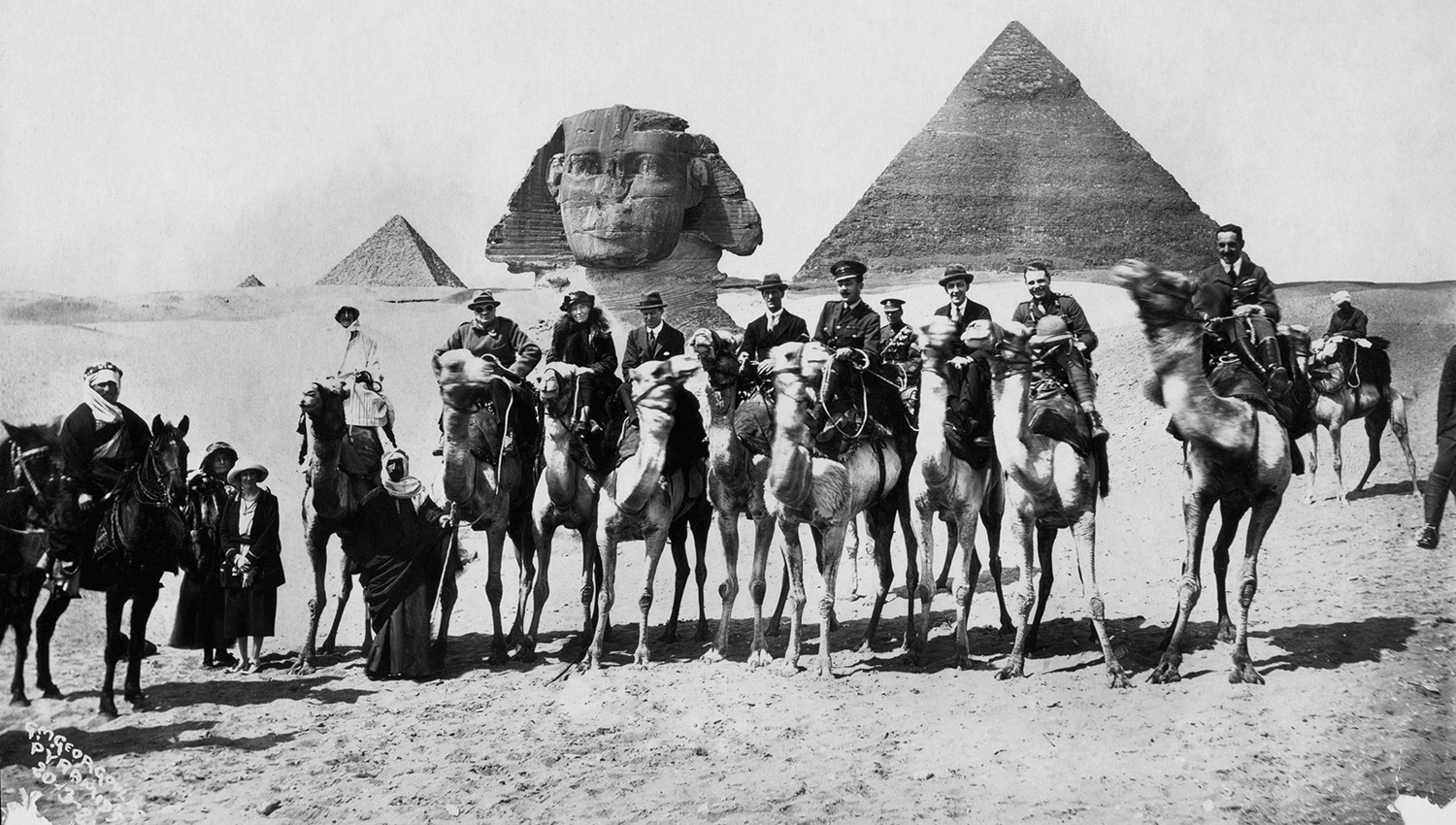

Bell was an adventurer who was attracted to daring and risky adventures. She quickly became interested in the native peoples in the Middle East, fearlessly traveling for years in a camel caravan on her own with a guide, mapping the terrain, and collecting a store of information about the tribes, their leaders, and their lives on the desert. She was particularly skillful in winning the trust of sheiks, even after one had kept her prisoner for 11 days. But after that, he sent her off with a bag of gold.

There seemed to be two sides to Bell; she was very intelligent and well educated and got along well with people who accepted her. She also got along well with the native Arabs, many of whom were desperately poor. Her biggest antagonists were men in the British government who could not accept a woman being in her position with influence, and one in particular tried to block her in every way he could. Despite his obstructions, she managed to retain the respect and admiration from the Arabs and high officials in the British government.

Bell was a conscientious scholar and researcher. The maps she made, the information she collected from desert tribes and sheiks, and the photographs she took were instantly valued and used by the British military and intelligence services. World War I was raging at the time, and Middle Eastern oil became a commodity wrestled for by other countries, particularly Great Britain and the U.S. Bell’s biggest disappointment after the war was over occurred when Britain did not honor its promises to the Arab states that they could be self-governing after the war.

Directors Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum have achieved a dynamic production with dramatic flair.

They continued their occupation, putting Arabs in advisory roles, rather than the other way around. The man most responsible for this was Sir Arnold ‘A.T.’ Wilson, the British civil commissioner in Baghdad, who had tried to thwart Bell’s efforts for years and looked down on the Arabic people. Nevertheless, she did play an important role in the establishment of the Iraqi state.

This film is based on letters between Bell and her correspondents, her diaries, and secret communiqués, and contains a wealth of information about her life and loves, the history of Iraq and desert tribes, and the politics of the time for that part of the world. She was an excellent writer of political communiqués and books, and her letters home to her father and stepmother were warm and complimentary. She frequently talked about missing being at home with them, yet even when her health was failing and her father begged her to return to England, she declined, saying she had to finish her work as Director of Antiquities, which was equipping a museum with Middle Eastern artifacts. The museum became the National Museum of Iraq, with one wing named after her.

But during this time after the war, she was out of the political arena, which had been so gratifying to her, and in the following eight years she experienced disillusionment and became seriously depressed. She died in Iraq on July 12, 1926, from a drug overdose, where she had chosen to be buried.

In excerpting material verbatim from Katherine Bell’s correspondence and photographs, Directors Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum have achieved a dynamic production with dramatic flair. By their utilization of vintage screen footage and fine actors voicing the lines of the characters, the film seems less like a documentary and more like a historical drama. The gifted Tilda Swinton delivers as the voice of Bell.

Final Thought

A Middle Eastern history lesson illustrating the critical role played by an astute and talented British woman.

1 thought on “Letters from Baghdad”

Dear Donna,

a wonderful review. Many thanks! Just a small note: in your last paragraph you say Katherine Bell instead of Gertrude Bell.

All the best,

Sabine